We welcome legendary drinks industry idea man David Gluckman to our pages. He’s perhaps best known for the creation of Baileys Irish Cream in 1973, with his then-partner Hugh Seymour-Davies. But David’s career has included many other blockbuster products, including Ciroc and Tanqueray Ten. In his unique and compelling memoir, appropriately titled That Shit Will Never Sell!, he also discusses the “ones that got away.” From time to time over his career, his gaze turned to rum, and here we have asked him to chronicle these tropical excursions. Though the Rum Reader is always interested in the creativity inherent in the technical side of spirits—fermentation, distillation, aging techniques—David details his style of pure ideation that was the primary genesis of many a bottle. — Ed.

As someone whose only experience of rum came from reading Hemingway and looking at Bacardí ads in 1950s American magazines, I can look back on a career where I helped create four sugarcane based brands. None was particularly successful, though one, I am convinced, should have been. Here is my story.

I started life as an adman, an account executive otherwise known as a “suit.” We were the people who schmoozed the client and made sure that things got done. We didn’t get to create anything.

It wasn’t what I signed up for. I had hoped to get a creative job. But because I could spell and had been to university, they made me into a suit. I did it for ten years. But I had to change. I wanted into the ideas side of the ad business. Or somewhere near.

I persuaded my boss to set up a new product development group. One of my first clients was a drinks company called IDV. They were medium-sized, owned J&B (then the biggest-selling Scotch in the U.S.), and were distributors of Smirnoff for Heublein outside the U.S. (Later on, in 1997, IDV merged with GuinnessUD and became Diageo, the world’s largest drinks company.)

When I started working for IDV in the late ’60s, they wanted to develop a white rum to compete head on with Bacardí, which was battling with Smirnoff to be the biggest spirit brand in the world. Bacardí was winning.

My client was an inspirational guy called Tom Jago. After an initial foray, which produced ideas like Caribbean White from Barbados, Rhum Louis from Martinique, and a rum called Bikini which would conjure up imagery of Ursula Andress emerging from the ocean in the first Bond movie Dr No, the company changed the rules.

IDV would build a distillery on the island of Mauritius in the southern Indian Ocean off the coast of southeast Africa. It was an action influenced by IDV’s South African company, which would manage the distillery and use South Africa as the launch pad for the brand.

After some exploration and debate with the South African team, we chose an idea inspired by a quote from Mark Twain’s book Following the Equator. We called our brand Green Island Rum and featured the Twain quote prominently on the label, where it remains to this day. It reads, “You gather the idea that Mauritius was made first, and then heaven; and that heaven was copied after Mauritius.”

Green Island was the first drinks brand I ever created, and while I still feel affection for it, the quality of my thinking improved as my career developed. It was a very good quality rum from an exotic, virtually unknown location. It matched up to Bacardí as a product. But to really compete it needed to do better than that.

There was an interesting spin-off from the Green Island development. Our plane to Mauritius broke down in Nairobi en route, and with a few hours to kill we went to visit IDV’s office in the city. The local managing director was intrigued with what we were doing and asked if we could create a brand which he could export from Kenya. It was an idle question, not a serious brief.

But I was particularly excited by the idea. Kenya, with its Hemingway associations and its reputation for wildlife and safaris, was probably the most marketable country in Africa at the time (1969). I suggested that we look at Kenya Cane. The idea for a cane spirit (a kind of unaged rum) came from my background growing up in South Africa. In the ’50s, before vodka had gained a foothold and white rum was virtually unheard of, the young person’s white spirit of choice was cane, a category pioneered by the Indians who worked the sugar cane fields in Natal.

Kenya Cane happened at about the same time as Green Island. While it is gratifying to note that both brands still exist today, neither has made much of an effort to venture beyond its national boundaries.

Things would get better.

It was now 1987 and I’d been creating drinks brands for 18 years. My most famous achievement was Baileys Irish Cream in the early 1970s. I’d also ventured into wine, beer, non-alcoholic drinks, and even Scotch whisky.

The then-global director of marketing at IDV summoned the development team and requested (again) that we look to create a head on competitor to Bacardí. He was an alumnus of the Mars Confectionery company and was looking for a brand with a “hard-nosed” marketing raison d’etre. It was a tough ask.

I did a lot of reading and a tiny amount of market research. Two focus groups carried out in London. And a lot of thinking.

And then it happened. My theory: If you want to compete with a hugely successful, global brand, don’t compete head on. Find a point of vulnerability and aim there.

My hypothesis? Bacardí was equally popular with men and women. Let’s ignore the female side and create a rum aimed more directly at men.

How to do it? First, up the ABV. Bacardí was 38%, our rum would be 43%. Significantly higher. Next, lower the sweetness. We would produce the world’s driest white rum. “Dry” would work for men.

In my reading, I found something else. Most rum was made from molasses. To consumers, this was thick, syrupy, gooey stuff. But there was another way to make rum. You could distill it from freshly-pressed cane juice. What better way to underpin a strong, dry white rum?

In my reading it was clear that Bacardí “owned” islands. Show a beach and a few palm trees and you were in Bacardí-land. In hindsight, an ad for Green Island would have been an ad for Bacardí.

So for the final part, we needed a new location. I looked at a globe of the world and traced around both tropics. I found Africa but there was too much trouble in Africa. Too many wars. And then I found Queensland, in Australia. It was nowhere like Bacardí-land.

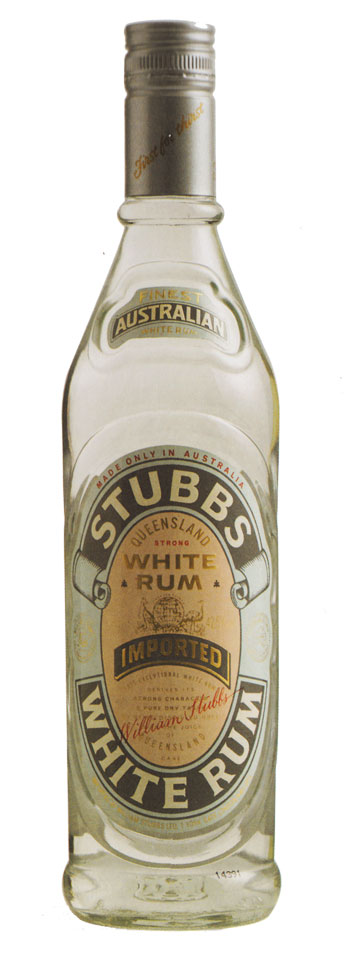

It was a perfect fit for what I was after. Australia was hot in the U.S. just then with a hugely successful movie called Crocodile Dundee. Its star, Paul Hogan, was the archetypal irreverent, macho Aussie. He would be the perfect ambassador for our brand. We called it Stubbs Australian White Rum. I thought it was the perfect response to the director’s brief.

It was. And it wasn’t.

We made two basic mistakes, both political, and they sabotaged the idea and sank the brand. One, we developed Stubbs on our own, without even consulting the Australian company who would eventually own it. So they dis-owned it. “It’ll never work in Australia,” they said. And Australia was a big Bacardí market.

Our second mistake was to present our potential U.S. importer with a fait accompli. And that was suicide. If Stubbs had achieved something, created a track record in Australia, they might have taken it on. But it was a naked, newborn baby and the Americans weren’t having it.

They appointed a single woman to push the brand in the U.S. She ploughed a lonely furrow for over three years. But it didn’t happen. And it was never going to happen.

I loved Stubbs. I thought it was a brand with a real chance against Bacardí. I remember the wonderful sales presentation material showing a bottle of gooey molasses alongside a pristine bottle of pure cane juice to highlight the difference and plug our strong, dry, clean Australian rum.

But sadly for Stubbs, the music died.

There is a postscript to all this. As my career with Diageo was drawing to an end in 2005, a new innovation team was mustering to go after Bacardí yet again. I was peripherally engaged and even managed a trip to Brazil for a couple of days. They were pursuing the fresh can juice idea which was part of the Stubbs proposition.

The brand eventually emerged after I’d gone. It was a rum from Brazil called Oronoco. It looked great. But from what I can gather, it’s become a collector’s piece rather than a serious contender. Bacardí can relax yet again.